"THE colour, the tannins, the complexity, the fruit", Christine Dupuy, the young, friendly owner of Domaine Labranche-Laffont, answers my question about what is so special about the Tannat grape variety.

|

| Domaine du Crampilh% Aurions-Idernes% AOC Madiran |

I can easily understand Christine's answer: Black with a reddish sheen, her 2001 "Vieilles Vignes" presents itself. A bouquet of dried mulberries, raspberries and spicy notes flows from the glass. One sip and a surge of tannin washes over my palate, still youthfully astringent but already with rounded edges. The wine has a very firm, concentrated body, it is powerful but not clumsy, the pronounced, well-integrated acidity takes care of that. The clear minerality carries the beautiful, very long finish. An outstanding wine with excellent ageing potential and a very good price-pleasure ratio. For 12 euros, you can get it at the farm. Or rather, you can get it, because apart from a few bottles that Christine has put aside, the vintage is completely sold out.

We are in the southwest of France in the Madiran appellation and here the clocks tick differently than in the rest of the wine world: Madiran, that is Tannat. The red wines of the neighbouring appellations of Béarn, Côtes de Saint-Mont, Tursan and Irouleguy (French Basque Country) also contain a high proportion of tannat. Nowhere else in the world is it grown as the main grape variety, nowhere else is it the basis for so many excellent, characterful wines. With one exception: Uruguay, where the emigrant Pascal Harrigue introduced and popularised the grape variety in 1870. He could not and would not do without Tannat, the wine of his French-Basque homeland.

|

| Christine Dupuy% Domaine Labranche-Laffont% Maumusson% AOC Madiran |

Tannat comes from "tan", which means "to tan" in the ancient language of the southwest, the Langue d'Oc. And tannins, or tannins, are abundant in Tannat. For a long time, tannat was considered a rustic, at best fruity and at worst alcohol-heavy tannin bomb. Rough and often bitter, wine from tannat presented itself not only in its youth, but over many years. The winegrowers in Madiran, however, loved and still love their Tannat. As early as 1788, the winegrowers of Vic-Bilh, which was the name of the Madiran winegrowing region at the time, applied to the Parliament of Navarre for recognition and protection of their wine as a "Cru". But it was not until 1910 that the "délimitation du terroir Madiran" was recognised as a result of their efforts. In 1948, Madiran for red wine and Pacherenc de Vic-Bilh for white wine were elevated to the rank of AOC by the Institut National des Appellation d'Origine des Vins et Eaux-de-Vie (INAO) under strict conditions. Madiran winegrowers were the first in France to commit to quality control of their wines with laboratory analysis and tasting. The first AOC decree of 1948 still prescribed 20 months of barrel ageing to give the hard, young tannins time to mature. In general, the INAO used to try to reduce the tannin content for all AOCs concerned to a maximum of 60% in favour of the supposedly nobler varieties Cabernet Franc (Bouchy) and Cabernet Sauvignon.

The turnaround came with Alain Brumont in the early 1980s. The son of a farmer was convinced of the potential of Tannat. Amazing, because he did not have the extensive, international experience in viticulture and the university education that today's top winemakers almost always have. His parents' estate, Château Bouscassé, was a typical Gascon farm with mixed agriculture, which also included some vineyards. He learned from his father and closely observed what was happening in the Madiran. In 1978, he took over the farm. With a sure eye for top sites, he bought run-down vineyards. He didn't care about the restrictions of the AOC. He replanted the vineyards with Tannat or, if there were old Tannat vines, brought them up to scratch and reduced the yields in favour of grape quality. In the cellar, he experimented with different maceration times, long barrel ageing in new wood and frequent soutirage (racking). His wines began to win prizes at regional competitions. Journalists entered his wine as a pirate in a competition and the nobody from Madiran beat most of the high-ranking growths from neighbouring Bordeaux. In 1985, he launched his top wine made from 100% Tannat, which immediately met with enthusiastic approval. Today, his "Château Montus Cuvée Prestige" and his "Château Montus XL" are among the most famous wines in France. The XL is only produced in very good years and there are only 4000 bottles. Due to Alain Brumont's efforts, Tannat is now counted among the "cépages nobles", the "noble vines".

|

| Alain Brumont% Grandseigneur of Tannat% Château Bouscassé and Montus% AOC Madiran |

What Alain Brumont intuitively did right is today, in a further developed form, the standard of committed winegrowers. Already in the vineyard, the Tannat is given a strict training. The very fertile variety is subjected to a rigorous yield restriction on older sites. In new plantings, smaller-grape clones have been used for years, which have led to a significant increase in the quality of the grape material at the expense of the yield. Where once 2000 vines/hectare lived in luxury and produced luxuriantly sprawling masses of grapes, today there are at least 4000 vines. The top producers go with 5000 - 8000 vines/hectare far beyond the minimum requirement of the AOC. They force the vine roots to seek water and nutrients in the depths and thus make them less dependent on drought stress and fertiliser. In addition, there is thinning out of the bones (blossoms), green harvesting, foliage work adapted to the season and weather, and manual harvesting with pre-selection already in the vineyard. This is how healthy, optimally ripened grapes end up in the cellar, the basis for great wines all over the world.

In the cellar, temperature-controlled fermentation on the skins ensures the optimal extraction of colour and tannins from the grapes. Some cellar masters even fish the grape seeds from the surface of the mash after a few days of fermentation. The rising alcohol content should not extract any unwanted 'green' tannins lurking in the pips into the young wine. This is followed by malolactic acid reduction, which is often followed by ageing in new barriques or in new 400 - 600 litre barrels.

Another innovation has also contributed decisively to the taming of the rough journeyman Tannat. Patrick Ducournau from Domaine Mouréou found that the softening effect that frequent soutirage has on rough tannins can also be achieved through targeted, controlled aeration of the young wine. Today, the technique of micro-oxidation is state of the art not only for Tannat, but for all tannin-rich red wines worldwide. By using pure oxygen and fine-pored ceramic filters, tiny amounts of oxygen can be "bubbled" into the wine directly in the tank or barrel as microscopic bubbles. The process is much gentler than multiple soutirage. This is because the young wine is strongly aerated by the racking and thus loses much of its fruity, aromatic charm. With micro-oxidation, the bouquet and aroma substances are retained and the tannins nevertheless become rounder, the wines are more harmonious and ready to drink earlier. Usually, micro-oxidation takes place in the phase between alcoholic fermentation and malolactic acid reduction. Young tannat wine, however, often flaunts such an abundance of impetuous tannins that the Madiran cellar masters often have to give it the reins of another micro-oxidation phase after malolactic fermentation.

Both techniques, micro-oxidation and frequent soutirage, can be found side by side. When it comes to long-term storage and ageing, many winemakers swear by soutirage. These wines usually consist of 80 - 100% tannate. Although they are already drinkable in their youth, they are often still rather inaccessible and usually only reach their peak after 10 or more years. Wines that are meant to be drunk young and fruity are almost always made using micro-oxidation. In Madiran, they are also blended with a high percentage of Cabernet Franc or Cabernet Sauvignon and some Fer Servadou (Pinenc) to make them more appealing from the start.

|

| Hills in the Pyrenean foothills characterise the AOC Madiran |

It is considered certain that Tannat comes from the south-west of France, the scenic quadrangle bordered by the Pyrenees to the south, with Andorra and Biarritz at its corners, and Cahor and the Gironde estuary to the north. It is very likely that the Tannat comes from the Adour valley or the area around the village of Béarn. Not only in the Bordelais, but everywhere in France's southwest there have been vineyards since Roman times. In the southwest, too, it was the monastic orders, especially the Benedictines and Cistercians, who became involved in viticulture after the Romans. It is certain that the pilgrims who passed through the Pyrenean foothills on their way to Santiago de Compostella from the 11th century onwards fortified themselves with the wine of the region before the strenuous mountain crossing. However, it is pure conjecture that they were already drinking tannat at that time.

In the 14th century, wines from Béarn, which historically includes today's Madiran, enjoyed great popularity in England. At that time, the southwest of France was in English hands and the English, then the Dutch, exported large quantities of wine to northern Europe via the Adour and Gironde rivers. The first written mention of the grape variety "tanat" is in 1783/84 in a survey by the administrator of Guyenne Dupre de St. Maur in the department of Gers.

Tannat has probably contributed significantly to the reputation of the "black wines" of the Southwest, which were used for centuries to enhance the thinner' clarets from the Bordelais. It is not for nothing that the grape variety is also called Bordelais noir. In 1841, a Monsieur Dartigaux-Laplante wrote that Tannat was almost exclusively planted in the Madiran because the grape variety would yield the largest quantity and the most beautiful, strongest colour.

From 1850 onwards, downy mildew, introduced from America, swept across France's southwest with its traditional tannat-growing areas, followed by the phylloxera disaster. Before winegrowers and vineyards had recovered, the Franco-German War came, followed by the First and Second World Wars, with bloodshed also among the winegrowers. It was not until after the Second World War that viticulture in the southwest recovered from the damage caused by nature and the consequences of war. Today, about 2500 ha of vineyards in France are under tannat. There are about 3800 ha in Uruguay. In Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Italy, New Zealand and the USA there are also a few hectares. In California, Georgia and especially in Virginia, the area under Tannat is even increasing. In Germany, no Tannat grows, but in Austria (Mittelburgenland) and Switzerland (Ticino, Valais) there are experimental cultivation areas and a few vintners use Tannat in their red wine cuvées.

|

| The ripe Tannat grapes hang on the vine like fat blue-black udders. |

Besides Alain Brumont's "Château Montus", another Tannat wine has recently made it onto the podium of international wine celebrities. Dr Roger Cordier from London's Harvey Institute for Circulatory Research was looking for an explanation for the "French Paradox": people from France, especially the south-west, eat fatter and yet die less often from the number one killer, the heart attack. That is why he tested 28 red wines for their blood vessel-protecting effect. The clear winner was a Tannat wine, the "Cuvée Charles de Batz" by Didier Barré (Domaine Berthoumieu, AOC Madiran), which subsequently made headlines as the healthiest wine in the world.

It is the high tannin content of the Tannat grape that is responsible for the heart-protective effect. Tannins are widespread in the plant kingdom and belong to the group of polyphenols. In particular, the berry skin of red grapes contains many polyphenols. Flavones and anthocyanins also belong to this group of organic substances. It is the anthocyanins that give the grape its red to deep blue colour. Anthocyanins and especially the flavones act as so-called radical scavengers and antioxidants. They protect cells from aggressive chemicals, metabolic products and oxidative stress, i.e. factors that lead to cancer, cell death and ageing. The high anthocyanin and flavone content of Mediterranean food with lots of vegetables and red wine is held responsible for the good health into old age of many people around the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. Tannat is also ahead in this category: it is so rich in flavones and anthocyanins that the berries and the wine made from them appear almost black.

Tannat is probably a historically quite old grape variety. It belongs to a group of related vines called Cotoïdes. The leading variety of this group is the Cot (Auxerrois, Malbec), the variety that was the most common red grape variety in southern France before the phylloxera disaster. Like the Tannat, the Cot produces deep-coloured, almost black wines.

In order to clarify the relationship and the historical age of grape varieties, genetic studies are now being successfully used. As with the proof of paternity in humans, it is also possible to compare grape varieties genetically to clearly determine the father variety and, of course, the mother as well as the closest relatives. And it is also possible to estimate whether it has been about 100 or already 1000 years since the grape variety was 'born'. In the case of the world's most important red grape variety, Cabernet Sauvignon, for example, we now know that Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc are the parents. No such information can be found about Tannat, although it too has been genetically studied. It may be that Tannat was simply not interesting enough due to its relatively low global importance so far. But it may also be that the relevant institutions have been very cautious with publications since Dr. Cordier's study revealed the outstanding cardioprotective effect of tannate. For a long time, the pharmaceutical industry has been panting after effective ways to preventively lower the risk of cardiovascular disease. A drug made from tannate that would drastically reduce the risk would be mega business. With the tannate pill in mind, all the research findings on the genetics, biochemistry and physiology of tannate are potentially worth cash.

|

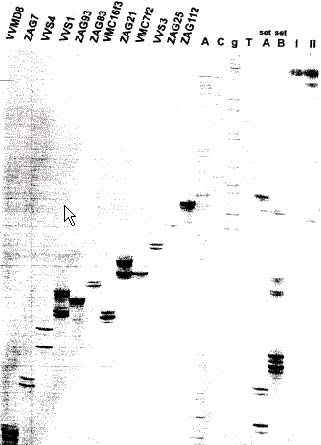

| DNA pattern of tannate (from: Vitis 43 (4)% 179-185% 2004) |

Already what is known so far shows that Tannat is also genetically a unique grape variety. Like almost all higher organisms, the grapevine has a double set of chromosomes, one set from the mother plant and one from the father plant. If we now compare identical locations on these two chromosomes (alleles), we can determine whether they are identical or whether they differ. In a study, scientists from Uruguay and Chile compared Tannat with other grape varieties. In relation to 15 commonly examined gene loci, 53% of the allele gene loci are identical in Tannat. No other grape variety can keep up. Cabernet Sauvignon has only 33%, Cabernet Franc and Chardonnay 20% and Pinot Noir just 6%. Its unique genetic make-up is probably also responsible for the characteristic bouquet, aroma and flavour of Tannat.

To part 2:

Tannat - the tamed powerhouse from France's southwest