Every self-respecting wine comes from the barrique. But now a few top winemakers claim that wine feels much better in stone and clay amphorae.

Winemaker-philosopher Nicolas Joly in Savennières on the Loire cultivates the generally underrated Chenin blanc, a white wine variety that can produce wonderfully subtle drops. The reasons why he entrusts his wine to wooden barrels - or more precisely, used barriques - are astonishing: "Should it be a coincidence that nature uses egg shapes to give life? Unmistakably, a barrel is something like an egg whose ends are capped. Its shape puts it in contact with its surroundings and concentrates a variety of influences inside it. What a pleasure it is to enter a room that is covered by a dome!

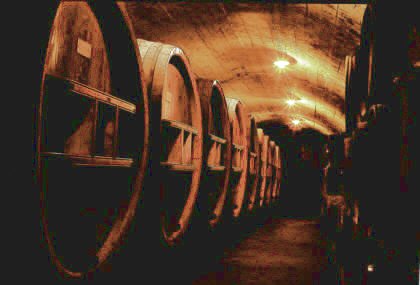

|

| Whether barrique or piece barrels - many winegrowers are convinced of wood. |

This always evokes a feeling of calm, and a different reality overcomes us. One gains distance from the oppressive cube shape that surrounds us almost everywhere. If you try putting a barrel next to a doghouse, it will only take a few hours for the dog to finally make this barrel its domicile." But is the wooden barrel - whether barrique or the 500 or 1000 litre piece barrel - really the best container for wine?

Hard as steel training

Riesling is the only one of the most prestigious grape varieties that has so far resisted the barrique. Even roughnecks have noticed that the elegance of this variety does not tolerate too much oak - and certainly not new oak. But winemakers are still not in complete agreement about the best method of cultivation.

|

| Many Riesling winemakers swear by this: steel tanks |

At the Robert Weil winery in the Rheingau, the Riesling lies solely in stainless steel tanks, where it ferments for between six and twelve weeks. Even after fermentation, the wine remains in the steel with strict temperature control. In this way, the patron alone decides what is to become of the Riesling. Like a pupil in a strictly run boarding school, he has no choice but to comply.

The situation is quite different at the Egon Müller winery in Scharzhof on the Saar. Egon Müller IV believes that the traditional 1,000-litre Fuder is far more suited to Riesling than a steel tank. "We only work with wood," he says, and immediately emphasises that the barrel must be as old as possible and consequently neutral in taste: "We bought the last Fuder about 50 years ago." At the Scharzhof, the wine is left to decide "where it wants to go". In some barrels, fermentation stops earlier, in others later. One could speak of an anti-authoritarian style of upbringing.

Wine slumbers in earth

Let's travel to Georgia, perhaps the oldest wine country in the world. In the fertile valleys of the wild Caucasus in the south-east of the country, sparkling clean and ice-cold water rushes down from the snow-covered peaks. Wine has been grown here for over 7000 years. In some of the remote villages, the clock seems to stand still. In autumn, the farmers fill the crushed grapes into their "kvevris". The "kvevri" is an amphora made of clay, some hold up to 3000 litres. They are all buried up to the rim in the clay soil that prevails here, and in such a way that they are additionally cooled by the numerous underground water veins.

There, the wine ferments and macerates until spring. Then the juice is skimmed off and poured into another "kvevri" previously cleaned with spruce bushes. Covered with a wooden lid and sealed with clay, the wine now slumbers in the cool earth in the shady cellar. There are families who have "kvevris" with wine that is over 50 years old. When such a treasure is lifted, the family patriarch still wears his Sunday robe with black felt hat and gathers family members and neighbours around him. He pours some wine into a shallow clay bowl and, after toasting "Galmajours!", drinks it all in one go.

Then it's time for the "keipi", the guest feast, the lively party at long tables outside the cellar. A "tamada", something like a master of ceremonies, is elected and he is assisted by a "merikipe", an assistant. They make sure that the glasses and plates are not empty, because that is the best guarantee that the toasts will be funny and courageous.

Renaissance of the amphora

|

| Amphora cellar of José Maria da Fonseca (Alentejo) |

Stone resonates

The Parisian research couple Anne Marie Amblard and Jean-Louis Gavard deal with questions in the field of energy and electromagnetic fields. Recently, as part of a private research project, the two investigated the properties of various materials used in the construction of wine containers. They determined the vibration frequencies of stone, concrete, wood, steel and plastic and compared them with the vibration frequencies of large wines.

It turned out that stone clearly had the highest response to the wine. Concrete also received very good scores. Wood followed in third place, but its vibration frequency was already far removed from that of the wine.

|

| The third highest resonance to wine - the wooden barrel |