|

| Album of a stranger from the Brockenhaus (Photo: P. Züllig) |

But the album aroused my interest. A collection? Memories of wine experiences? A diary in the form of labels? A documentation of wine taste? I know nothing about the owner, but imagine how the book got into the junk. It can't have been a collector, because collectors attach great importance to systems, to order, to completeness. With the best will in the world, I cannot discern any system on the 100 pages with about 300 labels. But systems of order are important for collectors, sometimes even more important than the collection itself.

It must have been a wine lover who wanted to document what he had just drunk with detached labels. I imagine that he has died in the meantime and that the lovingly tended small collection - it breaks off around 1995 - was given to the Brockenhaus by the heirs (after a certain period of reverence). What can you do with wine labels?

|

| Two of a hundred album pages (Photo: P. Züllig) |

For me, however, the album contains a lot of information and even more secrets that stimulate my imagination and provide many a clue to wine love and taste. My own thoughts and experiences emerge and are carried away into the large and yet so small world of wines. I know many names, I have drunk some wine - even if not the same vintage - at some point. And I ask myself, page after page: what all did the collector experience before he removed the label from the bottle? Were they similar impressions, experiences, feelings as I had when I drank the same or similar wines?

The first label bears the Bernese coat of arms and shows a castle: Erlach Castle, a historic town on Lake Biel, where the famous Rousseau Island (Peters Island) can be reached by land. The Swiss canton of Bern has no longer been a wine canton since Napoleon's invasion. With the loss of the old "subject territories" of the Lords of Bern, the large vineyards were also lost. Only on Lake Biel has the vine survived to this day. "The vineyard of the State of Bern", as the label reads, still belongs to the Canton of Bern, but has long since been transferred to private hands as a leasehold. The label does not bear a year, but the note "Golden Medal, Expo 1964" (Expo 64, that was the memorable Swiss National Exhibition in Lausanne).

|

| Bernese wine region on Lake Biel with Petersinsel (photo: P. Züllig) |

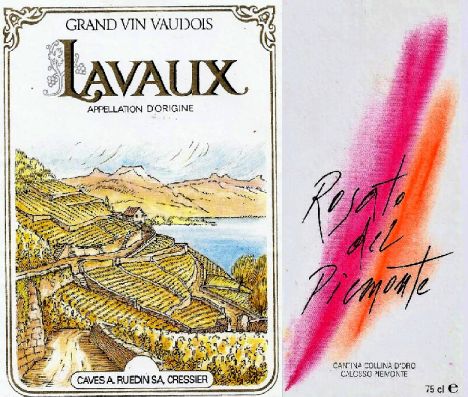

So our label game begins locally, in the 1960s. Already on the second page - who would have expected that from a Swiss? - a famous Moselle wine appears: Kröver Nacktarsch, vintage 1956 (Josef Milz) and 1957 (Richard Langguth). And a chapter of wine history begins to unveil itself: Back then, in the fifties, the "Nacktarsch" was also incredibly popular and loved in Switzerland. Right next to it, however, a completely different type of white wine: Dézaley ("Étoile de Lavaux"), a Chasselas from Lake Geneva and a Fendant ("Soleil du Valais") from the largest Swiss growing region, Valais - both vintage 1952, not sweet at all, but very dry.

Astonishing: Among the many Swiss and some Mosel wines - all white wines - there is suddenly - even before the French - a Grüner Veltliner (Kremser Sandgrube by Rudolf Kutschera und Söhne). Only later are two red wines documented, a Beaujolais 1956 and a Châteauneuf-du-Pape 1957 (both H. Deroye). But then the red wines increase, predominantly French, mostly Burgundy: Pommard, Clos de Vougeot, Mercurey (Parisote,1947!), Volnay, Gevrey-Chambertin (Daniel Roland). Italians, very common in Switzerland at that time, are only sparsely to be discovered, and only in the back part of the album. Italians at that time - in this country - were almost exclusively Chianti in demijohns (Fiaschetto), modest everyday wines, from today's perspective "just drinkable", i.e. not wines of which a wine lover would collect labels.

|

| Two labels% showing the taste of the 1960s (Photo: P. Züllig) |

As you leaf through the album, a good piece of wine history unfolds more and more concisely. Much is certainly coincidence or the individual taste of someone unknown. But - and I am sure of this - he has stuck into the album what was offered and sold at that time - in the period from 1950 to 1995 - what the wine lover often drank at that time and what seemed important to him to be remembered.

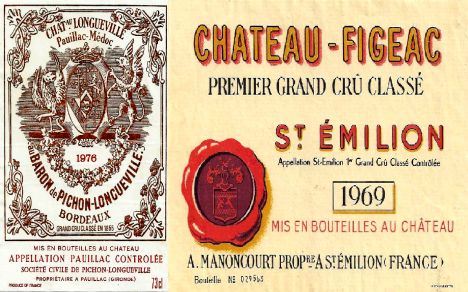

Anyone who takes the trouble to remove labels, dry them, smooth them out and glue them into a neat album must have a special relationship to wine, not only to the label; they must want to remember what wine experiences have lined up over the past forty years or so. Even though similar - or the same - wines appear again and again, a life with wine seems to develop and present itself. About a third of the way through the book, the first great Bordeaux appear: Baron de Pichon-Longueville (1976), Cos d'Estournel (1961), Figeac (1969), Clos Labère (Sauternes 1987). But they remain the exception, the exotics among the many wines. Just like the Italians, who are concentrated on two or three pages in the back of the book: Barbaresco 1979 (Gaja), Barolo 1984 (Giacosa), Vino Nobile di Montepulciano 1990 (Fattoria del Cerro).

|

| Two labels% that are still (almost) the same (P. Züllig) |

It is not simply pictures and writings, names and wines that are pasted and presented here. It is a zeitgeist that emerges from the album. The taste of the 1960s to 1970s is particularly evident in the picture and type design. But the content also lists wine tastes - and the availability of wines in those years. It is a book that explains more than many wine books that are on my shelf. It therefore deserves a place of honour, between the "Great Johnson" and the thick tome by Parker, because it writes a wine history of the "little man" who does not analyse wine, but obviously loves it and always wants to remember it.

Cordially

Yours/Yours