A week is short! Much too short, actually, for a region that surprises us with such diverse cultural, linguistic and culinary impressions, even though it is one of the five smallest in Italy.

Who would expect goulash, pancakes or slivovitz in Italy? The legacy of the different ethnic groups makes a culinary journey a small history lesson at the same time. We think back longingly to lunch at the Lokanda Devetak in San Michele del Carso, whose fine Slavic-Oster cuisine thrilled us just as much as the excellent veal shank at the restaurant La Subida in Cormòns.

The region's cuisine is as diverse as its mentalities. As a border region, the land has been subject to the influence of changing powers over the centuries, conquered and settled by the most diverse peoples. This has strongly shaped the character of the people. They are described as conservative, fearful and reserved. And indeed, the Friulians are not particularly warm at first encounter. Nowhere were we greeted and welcomed effusively, as is usual elsewhere in Italy. Most of the winegrowers were reserved and sceptical at first and only gradually thawed out during the conversation. "The people here hate change," says winemaker Adriano Gigante. Maybe that's why they are so attached to their traditions, hold on to the old and are shy towards strangers.

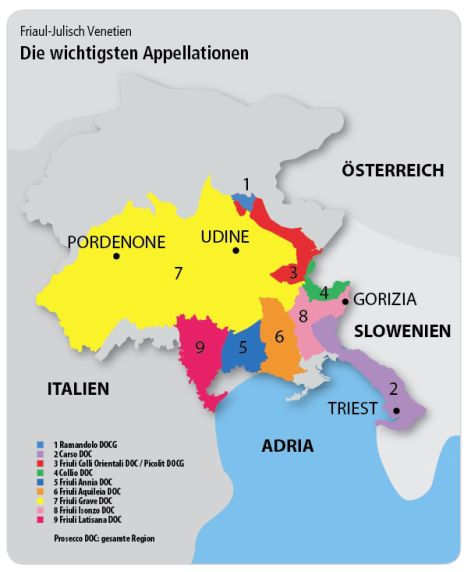

Languages and customs also change within a few kilometres. While the influence of Veneto is still strongly felt in the province of Pordenone, the Udinesi speak the deepest Friulian, and Slovenian is heard more often the further east you go.

The fact that not everyone in the region sees themselves as Friulians is something we only learn on the spot. "The inhabitants of the province of Pordenone actually belong more to the Veneto, and those from Gorizia and Trieste are not Friulians either," Damiano Meroi says with a laugh. In fact, the rivers that cut through the region in a north-south direction have the significance of natural borders. Whether it's the Tagliamento, Isonzo or Judrio: each one separated whole groups of people in the past and still represents a cultural barrier today.

There is much to discover here! The traveller learns that Friuli is not only Pinot Grigio, even if it is seen that way abroad, that Prosecco has meanwhile become an important source of income for the winegrowers in the plains, that the Friulano is strongly promoted by the region, but that the producers still clear it. That Ribolla Gialla is currently very popular and is being planted everywhere after it almost disappeared years ago. There is a lot going on in Friuli at the moment. Especially in white wines, there are changes that will shape the future image of the region. Our report looks at the current developments.

|

| (Source: Merum) |

Despite the diversity of its grape varieties, Friuli is best known abroad for Pinot Grigio, which, with just under 4,500 hectares (DOC/IGT), takes up a good quarter of the total area under cultivation. However, many winegrowers have a love-hate relationship with it. On the one hand, they need it, especially those who have a high export share. On the other hand, they are tired of being reduced to this variety, since they are more interested in wines like Friulano, Ribolla Gialla or the red Refosco.

Thus, when asked which wine is the most important for them, many winemakers answer with the counter-question: "Quantitatively or personally?" In few regions of Italy do the wine of which producers sell the most and the one they themselves prefer to drink have as little in common as here.

The extent to which a winemaker gives preference to international or autochthonous varieties is usually determined by the individual's economic situation. The larger the winery, the greater the pressure to sell corresponding quantities. And one thing is certain: it is not possible to sell millions of bottles of the little-known Refosco and Friulano.

Andrea Stocco from Bicinicco in the south of the Grave appellation explains: "In the 1960s, the winegrowers in Friuli began to focus on international varietal wines. At that time, there was no wine from Argentina, Chile, South Africa or Australia in Europe and therefore no great price competition. It was only in the 80s and 90s that the sales problems of Merlot and Cabernet began. We realised too late that we should have done more for the autochthonous grape varieties. The international varieties are so well established here that it's becoming difficult to change anything."

Friulian Pinot Grigio, on the other hand, has to compete additionally with that of neighbouring Veneto and Trentino. Both come on the market more cheaply in most cases because they are produced in larger quantities. Despite all this, Pinot Grigio is still in a relatively good position; demand in Germany and the USA seems unbroken. No matter in which appellation we spoke to the winegrowers: A large part cannot and will not do without Pinot Grigio, as it is often the ticket to a new importer.

Paolo Petrussa from Prepotto (Colli Orientali) is one of the few who do not produce Pinot Grigio, but he understands colleagues who do not want to do without it. He justifies this development with socio-cultural aspects: "Friuli was and still is a poor region with little industry. People here have always had to fight for survival. They simply cultivated what sold best and promised the highest yields: Merlot, for example, is much easier to care for than Schioppettino, Prosecco gives higher yields per hectare than Friulano... Little by little, the autochthonous varieties have therefore declined more and more."

Adriano Gigante (Colli Orientali) agrees and adds: "Many of the indigenous grape varieties were also very inaccessible - I'm thinking of the red Pignolo in particular - so they were replaced by the more pleasing international ones. Only with the introduction of vinification methods more suited to our varieties has this changed again."

Albino Armani from Trentino bought a vineyard in the Grave appellation about ten years ago. He says pragmatically: "I am basically of the opinion that winegrowers and grape growers should remain true to the autochthonous grape varieties of their homeland. But if the Grave growing region had relied exclusively on varieties native to here, viticulture would most likely have withered away."

To Part II of the report: "The Grave: Soy, Maize and... Wine"

Part III of the report: "Is Friulano the future?

Part IV of the report: "The wine from the hills"

Part V of the report: "Ribolla Gialla is booming"

Part VI of the report: "Barren coastal landscape"

All producers from Friuli in the wine guide

To the magazine article "White treasures

To the "BEST OF Friuli white" (PDF document)

This article was made available to us by the Merum editorial team. Find out more about Merum, the magazine for wine and olive oil from Italy, here:

To the Merum homepage

Order a free copy of Merum