On average, olives contain around fifteen percent oil. This content depends on the climate, the state of ripeness, the variety and the region. The task of the oil mill is to expose this oil, which is distributed in millions of microscopic droplets in the tissue of the olives, by grinding, to bring it together by kneading, to separate it from the solid parts of the olive by pressing and from the watery parts by separating. In the past, people were content with the highest possible oil yield, but today they also expect an oil mill to produce oil that is full-bodied and pure in tone. However, this brings new tasks for the oil mill: Not only must as much oil as possible be pressed from the olives, but also a maximum of non-fatty components must be extracted.

Before the oil droplets can be released from the olive cells by grinding, the leaves have to be removed and the olives washed. Whereas heavy, leisurely rolling millstones used to crush the fruit, this work is now done by noisy stainless steel machines. In these, the olives are processed into a pulp by knives, discs or beaters. The old oil mills are of truly historic beauty. In principle, they have not changed for centuries: If today it is potent electric motors that move the millstones, in the past it was water power and draft animals. Unfortunately, modern research findings show that this type of milling is outdated and absolutely unsuitable for producing quality. The highly sensitive olive pulp's quality is too much affected by this outdated technology. In modern oil mills, the Steinmühle, which not only ground but also kneaded, is therefore replaced by high-speed olive milling machines and sterile kneading troughs.

Kneading: Preparation for pressing

Kneading - formerly also done by the millstones - serves to bring together the oil droplets finely dispersed in the olive paste so that the highest possible proportion of the oil present in the paste can be extracted during the subsequent pressing. The olive paste is gently circulated for a certain time (20 to 60 minutes) in large heated stainless steel vats - more modern: vertical stainless steel cylinders - that hold several hundred litres.

Slowly, the oil separates from the watery components in the kneading machine. Sometimes you can even see a growing pool of oil on the surface of the pulp, shining yellow-green to dark green. To facilitate extraction, the pulp is heated, because the higher the temperature of the pulp, the quicker it is ready for pressing. Large oil mills are interested in processing as many olives as possible per working day. This is because the farmers pay for the pressing according to the weight of the olives. If the oil miller's work were paid according to quality, he would not heat the mash up to 30 °C, but would make sure that the temperature remained below 20 °C. This is because the purity of the oil is not guaranteed. This is because the purity of the oil depends heavily on the temperature in the kneading mills, especially in the case of injured olives - mechanical harvesting, olive fly.

A lot can happen during the kneading process. If the kneading takes place with air contact, the initially white-greenish or white-purple coloured paste turns increasingly brown. Just as the surface of a cut apple oxidises and the aroma degrades from "fresh-fruity" to "unfresh-dull" in a few minutes, so does the olive paste.

In contrast to the apple, which remains fresh under the unappetising cut surface, the olive pulp oxidises throughout its mass when it is stirred. Quality-oriented oil mills therefore ensure that the kneading process takes place under exclusion of air, so that the paste does not come into the press brown and oxidised through, but white and aromatic.

Advanced oil mills work with inert gas blanketing or negative pressure (vacuum pump). By kneading at low temperatures and keeping oxygen away, the risk of undesired oxidation and fermentation is greatly reduced.

In the kneading mills, however, not only the oil is to be made extractable, but this is to be enriched with the non-fatty ingredients of the olive. We are primarily interested in the antioxidants and the aromas.

In the kneading mills, however, not only the oil is to be made extractable, but this is to be enriched with the non-fatty ingredients of the olive. We are primarily interested in the antioxidants and the aromas.

In order for the polyphenols present in the olive as water-soluble glycosides - oleuropein and ligstroside - to become fat-soluble to a limited extent, they have to be split off from the sugar molecule by an enzyme present in the olive called beta-glucosidase. This enzyme is only activated by contact with the air when the olives are damaged and during the milling process.

The researchers also assume that the aromas only develop when the cells are destroyed, i.e. in the pulp. The olive oil in the olive - this is also just an assumption - hardly has any aromas

The enzyme lipoxigenase breaks down the fatty acids linoleic acid and linolenic acid into hydroperoxide forms with oxygen contact, from which the aromas arise in further enzymatic stages

Understanding these relationships makes it clear that olive oil is not merely the oily phase of the olive's pressed juice, but also the result of chemical-enzymatic processes that take place during extraction!

Pressing: Extraction of the oil

During pressing, the liquid part of the pulp (fruit water and oil) is freed from the solids (kernel, solid cell components, peel, etc.). While the pressing of grapes or mash does not pose any major technical problems, since the solids are of comparatively large dimensions and paths to the outside are always left open for the must or the wine, the pressing of a pulp, where the solids are very small and quickly block the drainage paths, is not technically easy.

The oil farmers of antiquity also had their difficulties in extracting the liquid from the olives. Pressing the pulp in a press basket - as with wine - led to unsatisfactory yields. In order to shorten the drainage paths for the olive liquid, people started to place numerous cushions filled with olive pulp on top of each other and press them out. Traditional oil mills still work this way today: The paste is applied as a thin layer to round press mats, which are stacked on top of each other like towers and put under pressure in hydraulic presses.

The oil farmers of antiquity also had their difficulties in extracting the liquid from the olives. Pressing the pulp in a press basket - as with wine - led to unsatisfactory yields. In order to shorten the drainage paths for the olive liquid, people started to place numerous cushions filled with olive pulp on top of each other and press them out. Traditional oil mills still work this way today: The paste is applied as a thin layer to round press mats, which are stacked on top of each other like towers and put under pressure in hydraulic presses.

From an economic point of view, there is not much to criticise about this system, the yield is good and the process can be almost completely automated today. For the quality of the oil, however, this method is a disaster. Due to their immense inner surface, the press mats provide the ideal conditions for undesirable oxidative, enzymatic processes.

While it is sad to see this centuries-old technology doomed to extinction, the qualitative difference between oils produced with this traditional method and the noisy, ugly, modern centrifugal presses leaves no choice. The stone millstones and the press mats are very beautiful to look at, but from a technical point of view they correspond to the state of oenology when wine was still made with the feet.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the machine industry made the first three-phase decanters available to oil mills: These were large centrifuges that separated solids, aqueous phase and oil at 3000 to 4000 revolutions per minute. This first generation still relied on diluting the pulp with lukewarm water. The most recent two-phase decanters, developed in the 1990s, manage practically without adding water and separate the oily olive pulp into oil and a moist, de-oiled pressed pulp.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the machine industry made the first three-phase decanters available to oil mills: These were large centrifuges that separated solids, aqueous phase and oil at 3000 to 4000 revolutions per minute. This first generation still relied on diluting the pulp with lukewarm water. The most recent two-phase decanters, developed in the 1990s, manage practically without adding water and separate the oily olive pulp into oil and a moist, de-oiled pressed pulp.

The purpose of adding water to the pulp is to simplify extraction in the decanter and is still the rule in most oil mills today. Where attention is paid to the highest quality, however, the addition of water is kept as low as possible and, if possible, even dispensed with. The reason for this is that some substances that are valuable for health and taste are water-soluble and, instead of remaining in the oil, are excreted with the water. In addition, the enzymes that occur naturally in olives are highly water-soluble, and their mobility increases as the water content of the paste increases. The availability of dissolved sugars also increases. This is all the more dangerous the later the new oil is filtered. Before the olive grower can take his olive oil home, some decanters have to clarify it in a separator - also a centrifuge. In this process, the oil is freed from aqueous impurities. Some modern decanters, however, work so cleanly that there is no need for further centrifuging.

Finally, the oil is weighed and the yield is determined. (The yield increases with increasing maturity. It can increase from 10 to 20 percent from the beginning of the harvest to the end)

Filtering and nitrogen: air and lees are harmful

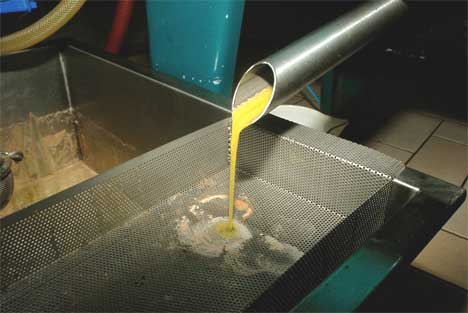

The oil that flows out of the decanter or separator always has a more or less pronounced turbidity. This turbidity consists mainly of cell water and cell components.

The dangerous thing about this turbidity is that it also contains the enzymes that threaten the stability of the oil. These enzymes quickly attack the oil, especially at rising temperatures, when the oil breaks down the triglycerides hydrolitically, which leads to the formation of free fatty acids. These in turn can be oxidised into volatile substances, ketones and aldehydes, when they come into contact with air. These substances give the oil the typical smell of rancidity.

Thus, not only the resulting sediment, but also the cloudiness of the fresh oil poses a threat to quality. Quality-conscious producers filter their oil immediately after pressing to ensure its stability. Contrary to popular opinion, filtering does not reduce the quality. On the contrary: filtering freshly pressed oils makes them more balanced and tastier. Fat-soluble substances such as aromas, polyphenols and other valuable by-products are not retained by the filter.

Extra virgin olive oil is rich in health-giving antioxidants. To protect the oil, these substances "sacrifice" themselves in oxidative situations - for example, when stored in open containers - and are consumed. If the content of healthy polyphenols and vitamin E is to be kept as intact as possible, and if the oil is also to be protected from becoming rancid, there is no way around covering the oil containers with an inert gas (nitrogen, argon) and thus keeping the atmospheric oxygen away from the oil.

Silly question: "Cold-pressed?"

The most frequently asked question about olive oil is probably: "Is the oil cold pressed?" The questioners don't realise that their technical question is a few decades too late and makes no sense today. In the past, oil millers were forced to extract the oil from the olive paste in several pressing cycles. First cold, then hot. They could only get the last bit of oil out by pouring hot water over the olive paste.

In the past, "cold-pressed" was a quality argument. Today, this no longer has any meaning: hot pressing is no longer used anywhere. Nevertheless, this "technical term" remains ineradicable on oil labels and in the minds of consumers. "Cold-pressed, ergo good!" is suggested.

But the quality argument "cold-pressed" is misleading the consumer. No oil can be extracted "cold"; temperatures above 15 °C are a prerequisite for problem-free pressing. At "cold" temperatures, pressing is very problematic and the oil yield is low: if the temperature is too low, oil remains in the oil pomace.

The olive paste should have a temperature of 16 to 27 °C at the moment it is introduced into the decanter. If the entire milling and pressing process is carried out at temperatures below 16 °C, the yield decreases noticeably; if, however, the temperature is raised above 32 °C - in order to speed up the pressing process or to increase the yield - the oil loses its typical flavour characteristics and tastes thin, watery and unpleasant; in addition, the composition of the ingredients that are valuable to health changes.

Since 2002, a legal provision regulates the claim "cold-pressed" (see page 100). Controlling the temperature in the oil mill is of the utmost importance for the quality of the olive oil. In the kneading tub, the olive paste can be heated to the desired temperature if necessary, because in the winter months, the olives may have a temperature of a few degrees above freezing point. Cooling is more difficult and unusual, although it would be important, especially in warm autumns and in the case of injured olives, to bring the paste below the critical temperature of 20 °C.

We prefer to leave the term "cold-pressed" out of our vocabulary; we should rather be suspicious when someone tries to impress us with "cold-pressed"! Anyone who uses this hackneyed term as a sales argument probably has nothing else to say about their oil

"Olive oil": actually a misnomer

Oil that is obtained solely by pressing olives and is otherwise marketed untreated may be called virgin (it.: Vergine, fr.: Vierge). A distinction is made between two quality levels: Virgin (Vergine), with slight imperfections, and Extra Virgin (Extra Vergine), which must be perfect not only analytically but also on the nose and palate.

If a virgin oil does not meet the legal requirements, it is called "lampante" and may only be sold refined - or rectified. Rectification consists of a series of physical and chemical processes: Neutralisation of the free fatty acids with the aid of strong bases, de-soaping by means of hot water, decolourisation with the aid of surface-active aluminas and activated charcoal, and deodorisation by treatment with hot water steam (220-280 °C) under vacuum.

The resulting oil is practically colourless, odourless and tasteless and deprived of many of its health benefits. The only reminder of the product's origin is the characteristic fatty acid pattern of olive oil (fatty acid pattern: ratio of fatty acids in the oil).

The chemically purified lampante olive oil may be sold as so-called "olive oil" if it has been blended with a proportion of virgin oil - not specified by law - and thus restored to a colour and aroma reminiscent of real olive oil.

Olio d'Oliva, Huile d'Olive or olive oil. The name suggests: oil from olives. But this is not the truth. "Olive oil" is not extracted directly from olives, but from a tainted product, namely lampante olive oil not approved for human consumption. To call this raffinate, obtained by means of industrial treatment, "olive oil" is actually deceiving consumers. The correct name for the category "olive oil" would be "rectified lampante olive oil".

Olive pomace oil: recycling of pressing residues

The olive pomace remaining after pressing still contains traces of oil. Depending on the pressing method, this can be three to six percent of the dry substance. However, mechanical processes - pressing or centrifuging - cannot extract this oil residue from the oil cake.

The oil mill therefore sells the pomace as a "waste product" to specialised industrial companies for further exploitation. In the past, these press residues were dissolved in hot water and pressed again (hot pressing), but by the end of the 19th century the industry had already switched to more efficient methods. Using solvents - today hexane, more rarely trichloroethylene - it extracts the last drop of oil from the pomace.

Before the oil pomace can be treated with solvents, it has to be dried. Sometimes this is done by direct firing, burning the residue left after chemical extraction.

The traces of the carcinogenic substance benzpyrene detected in cheap pomace oils in the recent past were combustion products that had settled on the oil pomace to be dried via the smoke and had not been sufficiently removed by the subsequent refining process. After drying, the preheated solvent is injected into the containers filled with pomace. The liquid obtained, a mixture of oil and solvent, must then be distilled: The highly volatile solvent evaporates and is collected in condensers; what remains is crude olive pomace oil. In order for the resulting delicacy to be allowed on our table as "olive pomace oil", it must be rectified and blended with virgin oil, just like lampante oil.

How olives and oil are handled

How the quality of the oil is influenced

Promoting quality:

Olives:

Oil:

Reducingquality:

Olives:

Oil:

Excerpt from the "Dossier Olive Oil" by Merum, the magazine for wine and olive oil from Italy.

The entire dossier (106 pages, Euro 9,-) can be ordered at www.merum.info.

If you would like to order a subscription to Merum, you can do so here:

Order Merum subscription

ALL PHOTOS IN THIS ARTICLE - COPYRIGHT

Jean-Pierre Ritler / MERUM